William King Wood

Born: 17 November 1897, Australia

Died: 28 November 1916, France

He comes when the gullies are wrapped in the gloaming

And limelights are trained on the tops of the gums,

To stand at the sliprails, awaiting the homing

Of one who marched off to the beat of the drums.1

This year, 2021, marks the 105th anniversary of the battles of the Somme, battles in which Australia lost more men in a single day than on any other day during the ‘war to end all wars’. Across Australia, there are families like mine who lost a loved one in World War One and, like me, their story has been written so that we continue to remember and honour those young men who died and are buried in foreign fields.

My uncle, William King Wood, was one of those thousands who died in France just over 100 years ago. He was born on 17 November 1897, the first child for John Charles (Jack) and May Lydia Wood (neé Phillips).2 He grew up at Kalbar, on a farm on the Burnett River on the outskirts of Bundaberg in Queensland. At various times, the farm grew sugar cane and other small crops and had dairy cattle. Willie attended Kalbar School, leaving in 1911 and worked as a labourer on the family property, Woodhouselee.

Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August, 1914, the commencement of World War 1. Young men across Australia rushed to enlist in what was seen as a ‘glorious’ adventure’ that, they thought, would be over all too soon. However, in 1915, following the first major campaign in which Australians were involved – in the Dardanelles at Gallipoli, it soon became evident to Australians that the war was not going to plan. By June 1915, when the seriousness of the Gallipoli campaign failure, and its resulting high loss of life, was brought home to Australia, debates focused on recruitment with around 2000 men enlisting in Queensland in November 2015.3

William King Wood enlisted in Brisbane on 13 November 1915. He gave his age as eighteen years and one month when in reality he was four days shy of his 18th birthday. He was five feet nine inches tall (1.75 metres), weighted 145 pounds (sixty-six kilograms), dark complexion with brown eyes and was Presbyterian. He was one of sixty-one men who volunteered on that particular day in Brisbane of whom forty-one were accepted. 4

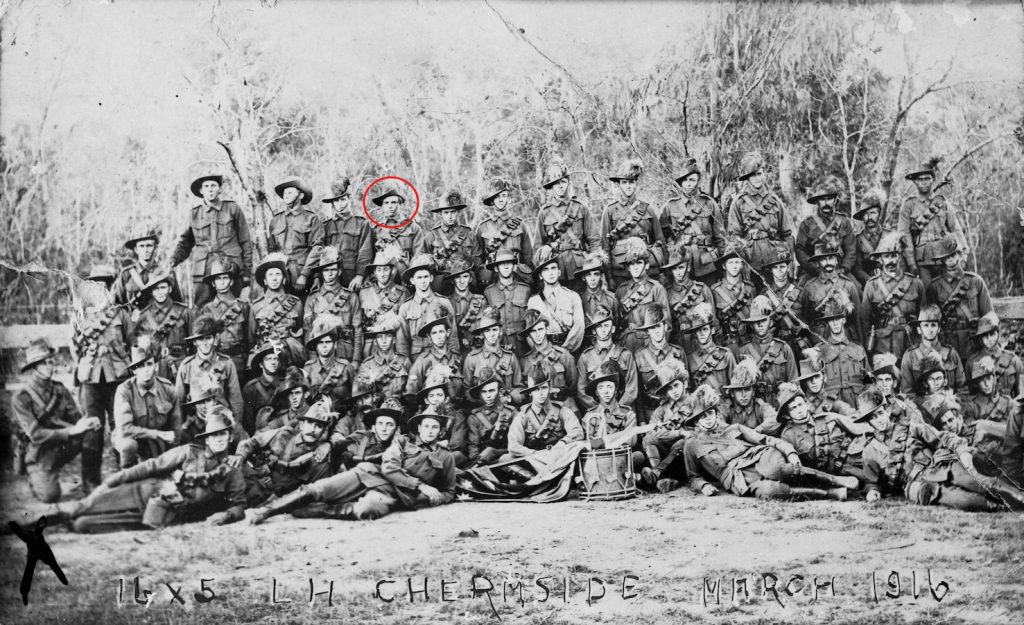

Following William’s attachment to the Fifth Australian Light Horse Regiment, Australian Infantry Force (AIF), 16th Reinforcements, his training immediately commenced at Chermside, known as ‘Tipperary Camp’.

Recruits for the Light Horse had to pass a very strict medical test before they were accepted and were generally required to take a riding test, which varied from place to place. At one camp, they had to take a bareback army horse over a water jump and a sod wall. In another, they had to jump a log fence. In the early stages of the war, complaints had been received that some men had not undergone any kind of riding test so, in order to maintain the quality of the Light Horse recruits, these tests became mandatory.5

The men were sworn in and issued with their uniforms – the normal AIF jacket, handsome cord riding breeches, and leather “puttee” leggings bound by a spiral strap. They wore the famous Australian slouch hat and a distinctive leather bandolier that carried ninety rounds of ammunition. When the Light Horse went to Egypt, Queenslanders, Tasmanians and South Australians wore the splendid emu plumes in their hats.

William regiment’s embarked from Sydney, New South Wales, on the HMAT A47 Mashobra on 5 April 1916. The Mashobra arrived in Fremantle on 13 April and took on supplies for the voyage across to the Suez Canal, arriving there around the end of April with the men marching into camp on 30 April.

On 9 May 1916, William’s record of service shows him as being taken on strength for the 2nd Light Horse Training Regiment. Formed in Egypt during March 1916, the 2nd LHTR was tasked with training incoming reinforcements while allowing the wounded and sick a place to recover before returning to active service. While training at Tel el Kebir, William transferred from the 2nd Light Horse Regiment to the Australian Field Artillery, established to support the newly formed 4th and 5th Australian Divisions. On the 28 May 1916, William embarked on HMT Corsican from Alexandria and disembarked at Plymouth, England on 12 June 1916 travelling to Bulford in Wiltshire, probably to have training at the Artillery Training Depot at Bulford Army Camp. Following his training, he was sent to France on the 21 July 1916. Here at Etaples, one of the base depots for the Australian forces, he was taken on strength, as a gunner, for the 4th Australian Division Artillery Details, undergoing further training and again subjected to strict medical tests. The men were also put through certain ‘gas tests’ to give them confidence against this form of attack, and were fitted with gas helmets.

From Etaples, the reinforcements were sent to areas just to the south and west of Ypres in Belgium, arriving on the 4 August. William continued as a gunner but was again transferred, in the field on 10 September, to the 4th Divisional Ammunition Column (DAC) where he was mustered as a driver in the field on 4 November 1916. The following days were miserably wet and cold, with heavy rain and dreadful conditions. Mud was in some of the billets (usually in barns). On 13 November 1916, the 4th DAC left Vlamertinghe and moved to Wirpenhoek. For the next ten days, the 4th Divisional Ammunition Column marched in bleak conditions from Wirpenhoek to Montauban (now known as Montauban-de-Picardie, near the town of Albert). On today’s roads, it is a distance of about 140 kilometres and would normally take about an hour and a half to drive it. The Divisional war diary reports that the conditions at this time were deplorable – the rain caused the road conditions to become quite boggy and ammunition was deteriorating. Carrying packs and ensuring that the horse and mule wagons were not damaged if they became bogged, the soldiers ploughed through the mud.

Men in the 4th DAC, including William, were sent to collect the ammunition from advanced positions about two kilometres from the German line in the Delville Wood area. As a driver, William’s job was to ride one of the horses or mules attached to wagons, to bring up the ammunition daily and nightly across the mud, a necessary but dangerous and difficult task.

On 28 November at about 10.30am, William King Wood, and at least eleven other men were either killed or wounded when a dud shell exploded.

The 4th DAC War Diary for 28 November records:

28 Nov Montauban:

No 2 Section, in collecting 13 pr shells from ammunition shelters at S4C to return them to railhead, sustained casualties of 4 men K: 8 Wd (1 ret to duty): 3 horses & 24 mules killed or destroyed. Witnesses mostly agree in presuming a mule kicked a loose heavy shell or ‘dud’: There was shelling by most lines at the time.

William sustained serious wounds from the explosion – fractures of the fibula and tibia, right thigh and left leg. He was taken to No 1 Main Dressing Station at Becordel which comprised one field ambulance with three or more tent sub-divisions – it could accommodate between 400 and 500 patients and contained three large operating tents each with three tables.

Four men were killed almost instantly, William died later that day and at least two other men died two and three days later. The four other men who were killed were like him, young men who had joined a Light Horse Regiment and transferred to the 4th Divisional Ammunition Column as a driver.

Known as Woodsie by the men in his unit, later accounts describe William as young and round faced. Aged just nineteen years old, having had his birthday in the field on 17 November, he was buried the following day in the Becourt Cemetery about three kilometres from the small village of Albert.

The news about William’s death was received at Kalbar early in the morning on Saturday, 16 December 1916. Reverend David Galloway, the Presbyterian minister in Bundaberg, arrived at Woodhouselee with the dreaded telegram, informing Jack and May Wood of the death of their son.

That Saturday was also the day of the Kalbar School picnic and the sad tidings cast a gloom over the day, as all there knew William and his family and all felt the loss. The Wood children went to the picnic leaving their parents to mourn at home. In the afternoon, William’s sister, Maisie aged four, the youngest of the family, dressed as a Red Cross nurse and went to all present at the picnic collecting money (over £2) for “Australia’s wounded heroes”.6

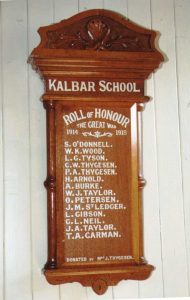

Later in the afternoon, it had been planned that Mabel Thygesen would donate a beautiful silky oak honour board to Kalbar School, but due to the sad news, she was not able to attend. She remained with her sister May and brother-in-law Jack when she heard the terrible news. (Mabel was to also lose a son at Ypres in 1917.) Mr WG Gibson, of Bingera Mill, did the honours of unveiling the board which had fourteen names inscribed on it. William was the second named on the board but the first to die.

At the end of the war, the people of Kalbar and surrounding district contributed funds to erect a memorial to the four young men who had been killed. In 1920, the memorial was placed next to Kalbar School and when the school closed, the memorial was relocated to the South Kolan State School.

The inscription on the memorial reads:

In honoured memory of four boys, past scholars of Kalbar S[tate] School killed in action during the Great War 1914-1919. WK Wood killed 28th Nov 1916, aged 19; PA Thygesen killed 31 July 1917, aged 23; LCR Tyson killed 16th Aug 1917, aged 33; JA Taylor killed 4th Oct 1917, aged 32. They rose responsive to their country’s call and gave for her their best – their lives – their all.

William was only at the front line for four months. He did not distinguish himself in any way—he did not win any medals for bravery, nor was he mentioned in despatches. He was one of thousands who gave their lives and did so without fanfare or flourish.

Australia lost its youth and one family lost a beloved eldest child and brother, aged only 19, now buried in a foreign land.7

Quote FOFMPCS21 to receive a 20% discount on a 12-month PRO subscription at Findmypast.com.au.

Disclosure: I am a Findmypast Global Ambassador and receive a free PRO subscription from the company.

Endnotes

World War 1 service records are digitised and are available at the National Archives of Australia.

War diaries are available at the Australian War Memorial.

Red Cross records from World War 1 have been digitised and are available at the Australian War Memorial.

Findmypast collection: Australia, Military Commemorative Rolls & Rolls of Honour.

1. O’Brien, John. Around the Boree Log and The Parish of St Mel’s. (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1921). (When I was young, one of my father’s favourite books was this anthology by John O’Brien (Father Patrick Hartigan). This is from one of his poems, Ownerless, about a horse who comes every day to wait at the paddock rails for his young owner who went to war and who will never return.)

2. QLD Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Birth certificate for William King Wood, born 17 November 1897, registration number 1898/C/516.

3. C.W. Bean, Volume III – The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916 (12th edition), Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416847.

4. Morning Bulletin, 16 November 1915, 7.

5. The Mounted Soldiers of Australia. Australian Light Horse Association, https://www.lighthorse.org.au/resources/history-of-the-australianlight-horse/the-mounted-soldiers-of-australia.

6. Bundaberg Mail, 21 December 1916, 3.

7. About 62000 Australians were killed in WW1 out of a population of only 4 million people. Almost 420000 Australians enlisted for service, representing 38.7% of the total male population aged between 18 to 44. At almost 65%, the Australian casualty rate (dead and wounded – proportionate to total embarkations) was among the highest of the war.

A sad story Cathie, but really interestingly written. So young 😪

It is so sad and there were so many just like him.

Cathie – very nice post in William's honor. I'm happy for you that you have photos of him. So incredibly sad to think of the young men lost in wars over the centuries. I too lost an ancestor at the Somme and wrote about him. I later found a photo of him. http://www.michiganfamilytrails.com/2019/03/military-monday-frank-gillespiekilled.html

Thanks very much Diane. Your story about Frank is also so very sad, particularly because Frank had a wife and child. I am so glad you found a photo of him.

Dear Cathie,

This is a poignant tale about your ancestor, and a fitting tribute to his memory. I. too, lost two great uncles in the war. Both were British soldiers and both died in 1917. For the benefit of my family and descendants, I have written and distributed the story of one and am writing the story of the other – whom I only recently discovered thanks to Ancestry.

I also write stories about WW One soldiers from a Melbourne suburban area . some were in the Light Horse. See the blog of empirecall.pbworks.com if you are interested.

Have you lodged your story on the RSL virtual War Memorial? You should. The Australian War Memorial is not interested in second-hand stories, so the RSL memorial is, I think, the best place for them.

Regards,

Rod

Thank you very much for your kind comments Rod and for the link to The Empire Called and I Answered site which looks interesting. I haven’t lodged my story with the RSL yet and should do so. I have a much longer version of this post which outlines more of the drudgery of the march from Ypres to Albert and the time spent in Egypt. I would be interested in reading your stories too.

I was interested to read of the riding test for the Light Horse.

So many young men killed and wounded. Such a loss.

Anne, what is also interesting is that many of the young men who enlisted in the Light Horse were later transferred to the Ammunition Columns, because they knew how to handle the horses and the mules.